Server-side rendering React in OCaml

server-reason-react is an implementation of react-dom/server and some of React's internals in OCaml. Its purpose is to render HTML markup from the server for a Reason React application natively.

This post provides an overview of some of the concepts of the library, what it means to render React in OCaml, how we use it at ahrefs.com, a benchmark against a Node equivalent, and the future of all of this.

If you are not familiar with Reason or OCaml, it's fine. The purpose of this post is not to convince you to learn or try those languages but rather to share something I built that I'm passionate about.

I will try to explain most concepts for any developer with experience in React. Don't be scared by any niche language/technology mentioned here since I will introduce them as we go.

The first piece of context to follow this post is to introduce Reason and OCaml for those who are not familiar with them:

Clarity about Reason and OCaml

Reason is a language built on top of OCaml, they share the compiler, the type-checker, and most tooling around. It was created by Jordan Walke to allow JavaScript developers to enjoy OCaml. Back in the days (when TypeScript was not as popular) many members from the JavaScript community were interested in Reason.

OCaml is a type-safe and robust language that empowers a functional style with powerful inference. It provides a unique balance of performance, maintainability, and reliability.

Despite being a niche programming language, OCaml has made an impact on modern programming languages and language tooling. The first versions of Rust were implemented in OCaml and Meta’s Flow JavaScript type checker as well, also used as the basis for ReScript an offshoot programming language which offers compiled statically typed code into JavaScript. Nowadays, OCaml is a solid option for a general programming language backed by trade firms, blockchains and SaaS companies.

I often refer to Reason/OCaml interchangeably since they are the same for me. Reason has a different syntax that should feel familiar to JavaScript developers, but the “engine” is the same as OCaml.

ahrefs.com

At ahrefs, I'm a Software engineer working on tooling. I work on maintaining the design system, styled-ppx, helping with Melange and now on server-reason-react.

ahrefs is a comprehensive SEO toolset that provides data-driven insights and competitive analysis for digital marketers and businesses. With one of the best crawlers of the internet, we recently launched a search engine called Yep.com with the goal of providing a better revenue-sharing model.

It's written mainly in OCaml and Reason (there’s a bit of Rust and C++/D) with a monorepo containing more than 1M lines of code. We value type-safety, maintainability and performance.

The frontend parts of ahrefs are the dashboard (app.ahrefs.com), the public website (ahrefs.com), a tiny website called wordcount.com and Yep.com.

The problem

One of the initial problems with our main React application (app.ahrefs.com) was the client-side rendering.

The canonical example of this problem happens on the Header. We had to load a bunch of contextual data such as user, permissions, billing, tokens and theme. Running all of those requests on the client creates a request waterfall and often our users use more than one tool at the same time, where navigating between those is not an optimal experience. Navigation would be slow, “flashing” the header (and the entire app) while mounting each page each time can be annoying and a waste of the same requests.

To address those issues, we implemented server-side rendering for the static parts: a “shell” app and injecting the data as regular scripts with serialized JSON. We used Tyxml, a library that generates HTML from OCaml, for creating these static templates.

It improved the user experience by a lot, since the HTML served contains the static part of the app, so the browser can cache it locally. But, we quickly encountered a new problem: having two separate implementations of the same component. The client version, written in React and the server version, written with Tyxml.

- Not easy to share implementations or even styles between the two

- Keeping both versions in sync with different data-requirements is too much hustle: Ensuring the server version of the component functioned correctly without data and the client one mounts on top with the interaction

The resulting tech was difficult to maintain, deterring developers from making significant changes. While this solution was adequate for some time, we sought a more scalable approach for our other frontends.

To address some of those problems, Javi (one of my coworkers) experimented to mix Tyxml and ReasonReact and published the experiment in his blog: javierchavarri.com/react-server-side-rendering-with-ocaml

In addition to server-side rendering (rendering in each request), we needed a different strategy for our static pages, such as Server-Side Generation (what Next.js calls Incremental Static Regeneration). Running a rendering step at build-time and populate state on each request.

Ultimately, our goal was to use the same client components from our design system in these server templates.

First approach

The common solution to this problem is to go with a node-based solution, such as Next.js, gatsby or Astro. After using gastby and react-snap for a few years and a proof of concept with Next, we weren’t satisfied with any approach.

Pre-rendering (SSG) with Node

Running the pre-rendering step during the build and serving them via our backend in OCaml.

This solution couples the build process (running in CI) with the runtime (the production and staging servers). Increased the complexity on how we were serving those static files, and how those static files became polluted with data (also known as hydration).

- Templates could be unsafe to hydrate and error prone

- Needed to generate templates for each language (currently 17) and upload them on CI

- Running the pre-rendering on CI made a weird combination, pre-rendering required to couple our OCaml backend with HTML files and be aware of purging the cache

Running Node with SSR on production

The other solution is to serve the application by Node and using OCaml as API.

Placing node in front is a very common architecture that works wonderful in some teams, but there are still some drawbacks when using Node in the backend for ahrefs.

Most of our API consists of fetching from different data storages and shuffle this data to serve it. Some of those problems make it non ideal for us:

- Single-threaded nature: Node.js is inherently single-threaded, which can lead to performance issues when dealing with high-concurrency or CPU-intensive tasks.

- Node.js isn’t the best player at memory consumption. SSR applications can be memory-intensive, potentially causing resource constraints in production environments.

- Additional burden on DevOps, as they were not happy learning another language and framework to manage, with emphasis since it’s the entry-point for users.

- Type-safety concerns: Ensuring type-safety would require either using TypeScript and maintaining separate type definitions or using Reason and compiling it to JavaScript. However, the Node.js’s bindings aren’t my favorite part of Reason.

- Might lead to some duplication of logic —e.g. authentication— on both our Backend and Node.

- Switching a request from the server to the client (or the other way around) can be challenging, potentially leading to increased complexity and maintenance efforts.

After discussing with my coworkers and specially Javi with his explorations on Tyxml and ReasonReact, an idea appeared: it might be possible to use the exact same code from the client in the server, if we re-implement or stub some stuff here and there.

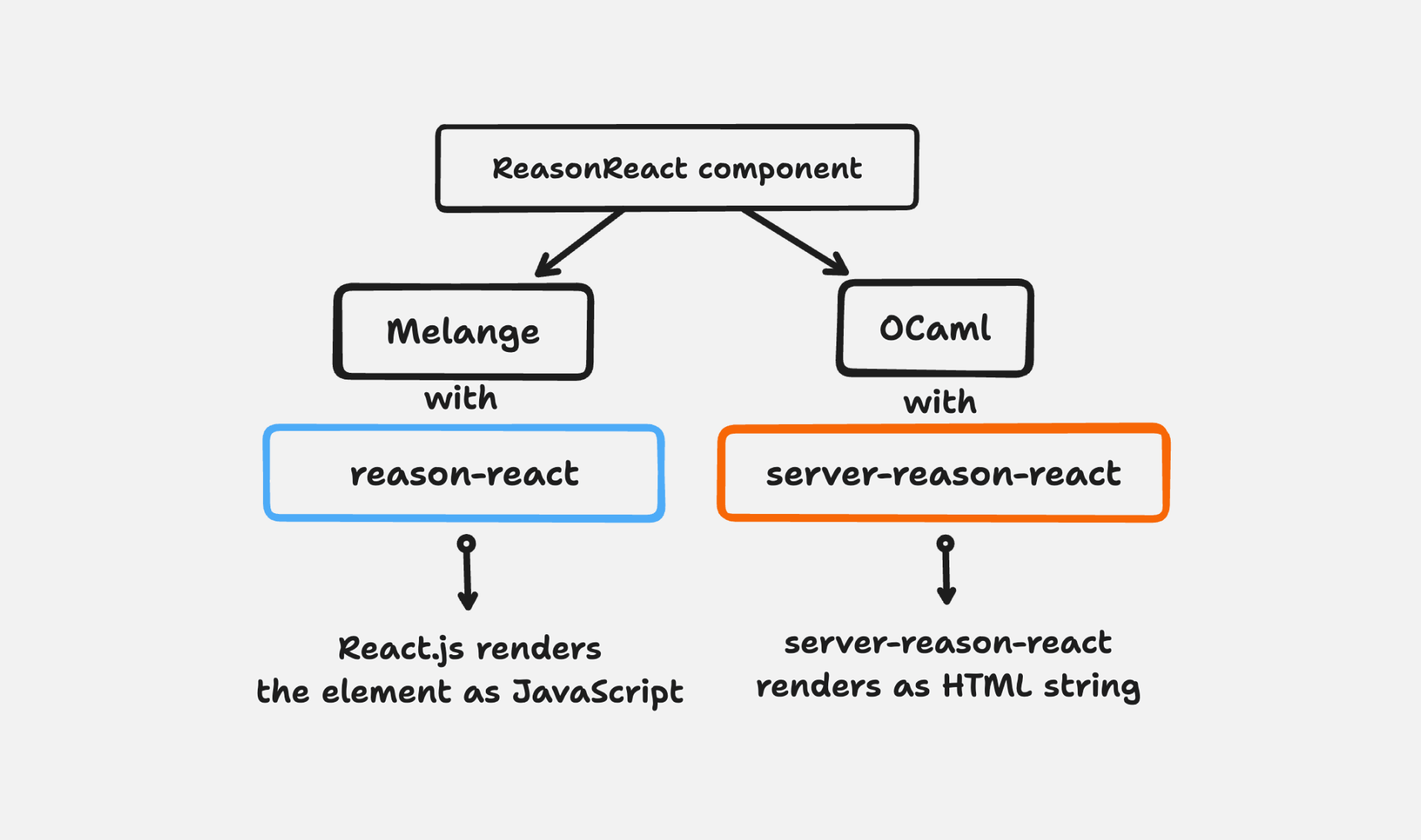

We could have the same approach on how the JavaScript ecosystem do, running the exact same React components on the server but with the twist of running native code on the server while compiled JavaScript on the client.

How hard it would be?

Enter server-reason-react

reason-react

The Reason parser comes with the JSX transformation out of the box, so JSX expressions are compiled down to function calls. No need to use babel, esbuild or vite in Reason.

reason-react are a set of bindings to the JavaScript version of React. So, a tiny layer for the type-system to tell the Reason code the right interface of those hooks, createElement calls, and any React API, similar on what .d.ts modules are in TypeScript or FFI in Rust.

The repository lives here https://github.com/reasonml/reason-react

What’s server-reason-react?

server-reason-react is a re-implementation of ReactDOMServer (react-dom/server) and some parts of React itself to generate markup from a React component but written in OCaml.

More precisely ReactDOM.renderToString and ReactDOM.renderToStaticMarkup

To make sure this ReactDOM can represent all kinds of nodes in React: components, elements, Fragments, Providers, Consumers. Here's the node variant type that represents all of them:

type element =

| Empty

| Text(string)

| List(array(element))

| Fragment(element)

| Html_element(string, attributes, list(element))

| Component(unit => element)

| Provider(element)

| Consumer(element)

| Suspense({ children: element, fallback: element })type element =

| Empty

| Text(string)

| List(array(element))

| Fragment(element)

| Html_element(string, attributes, list(element))

| Component(unit => element)

| Provider(element)

| Consumer(element)

| Suspense({ children: element, fallback: element })It's a variant type (aka union or ADT) and it matches with what React internally uses with Symbols. It's a recursive type (rec) since it references itself.

The actual string generation is done by traversing the component tree to generate specific HTML representation of each node. In each "node" takes into account a few details such as serialize DOM attributes, process inline styles, encode HTML and a few React particularities (such as dangerouslySetInnerHTML or hydration hacks).

/* A pseudo implementation of renderToString to ilustrate the mapping between

components and HTML representation.

Note: `++` is a string concatenation operator */

let rec render_to_string = node =>

/* ... */

switch (node) {

/* ... */

| Html_element({ tag, attributes, _ }) when Html.is_self_closing_tag(tag) =>

"<" ++ tag ++ attributes_to_string(tag, attributes) ++ "/>"

| Html_element({ tag, attributes, children }) =>

"<" ++ tag ++ attributes_to_string(tag, attributes) ++ ">" ++

List.iter(render_to_string, children) ++

"</" ++ tag ++ ">"

| Component(component) => render_to_string(component())

| Text(text) => Html.encode(text)

| List(list) => Array.iter(render_to_string, list)

| Consumer(element) | Provider(element) => render_element(element)

| Suspense({ children: _, fallback }) => render_element(fallback)

}/* A pseudo implementation of renderToString to ilustrate the mapping between

components and HTML representation.

Note: `++` is a string concatenation operator */

let rec render_to_string = node =>

/* ... */

switch (node) {

/* ... */

| Html_element({ tag, attributes, _ }) when Html.is_self_closing_tag(tag) =>

"<" ++ tag ++ attributes_to_string(tag, attributes) ++ "/>"

| Html_element({ tag, attributes, children }) =>

"<" ++ tag ++ attributes_to_string(tag, attributes) ++ ">" ++

List.iter(render_to_string, children) ++

"</" ++ tag ++ ">"

| Component(component) => render_to_string(component())

| Text(text) => Html.encode(text)

| List(list) => Array.iter(render_to_string, list)

| Consumer(element) | Provider(element) => render_element(element)

| Suspense({ children: _, fallback }) => render_element(fallback)

}To be sure it supports full render and hydration the same way as React does, I migrated all tests from the ReactDOM's server test suite.

With all of this solved, on the server rest of React such as hooks, portals or any other APIs were trivial in comparision. Most hooks do nothing: useEffect don’t run. useState is only setting the initial value, all setStates are ignored. useCallback creates the function once (and probably never called). useMemo runs and gets the value.

One difference from my implementation is about doing a single pass on the React tree, while React.js does multiple passes, but it’s on them to change it: https://github.com/facebook/react/issues/25318

With all of this done, we can return those strings as HTTP responses, and we have a server-side rendering solution working!

Benchmark

The main question I got while I was implementing this was about performance.

The theory said that a compiled language (OCaml) should over-perform an interpreted one (JavaScript in node), even when v8 (the engine that node runs on top) is working tirelessly to optimise it. There have been many benchmarks to prove it, but does it holds true here?

I was curious too, but, as explained above it was not the impetus for server-reason-react creation. In fact the implementation isn’t very optimised, and not even profiled. It does try to minimise allocations and CPU cycles but there hasn’t been any performance work so far.

I made a small micro-benchmark before pushing to production to ensure there wasn’t any regression and prove how much gain are we talking about (against a Node and bun solutions):

We compared the performance of three stacks in terms of latency, requests per second (req/s), and transfer rate.

| Req/s | Avg Latency | Transfer/s | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Node.js (with Express) | 7.2k | 30.98ms | 8.25MB |

| Bun | 10.3k | 24.32ms | 17.5MB |

| server-reason-react (with OCaml) | 64.8k | 6.21ms | 155MB |

It shows an approximate improvement of x10 over Node and x6 over Bun.

All tests are run on local under my MacBook Pro (13-inch, M1, 2020), and the benchmark data comes from a demo repository: https://github.com/ml-in-barcelona/fullstack-reason-react-demo/tree/main/benchmark.

Even thought the benchmark is not very scientific and it can lie in terms of micro-benchmarking it shows the potential of this approach and validates the theory.

Status

It’s deployed to all users at app.ahrefs.com since February and planning to use it for all frontends. Although, it’s not ready for consumption. The lack of documentation, the shape of the libraries and some missing APIs makes it hard to use and I don’t recommend relying on it.

It's open-source and the repository lives in GitHub, check it out!

Even with all of this, if you are still interested feel free to contact me in Discord or Twitter, and open issues on GitHub.

What it enables

I got a little deep into some of the details about how it works for the curious minds, but the implementation doesn’t matter much. What matters are the consequences:

Same code for frontend and backend

The same code gets compiled to Native and JavaScript (thanks entirely to Melange). As far as I know, it can’t be done in other native languages such as Rust or Go, there are many of similar solutions but they don't cross-compile the same code.

It enables full-stack applications written in Reason. It’s not a matter of "one language to rule them all", but rather simplicity.

Simplicity on shared data types, one learning experience, one toolchain, one set of rules, etc. Even thought sharing code has some detractors (and with good reasons) once you face the troubles of maintaining big pieces of code between stacks, you appreciate a single language after-all.

Performance is much better

Performance is critical for any SSR solution, not only the rendering engine itself but the platform you are running as well. Not only the number of requests per second it supports or the memory footprint. Among many performance issues, one that stands out is the slow start. The slow start of a Node application is a barrier for current solutions. Often this problems is addressed by changing the architecture of your application by utilizing Edge computing, or a blocker to run SSR in development.

Here is an example of a performance benefit from OCaml. Some OCaml-based frameworks are fast enough that it can boot for each request and tear down when the session finishes. On the other hand, this is much more challenging to do with Node.

Maybe with a more performant approach we can solve some of the problems from SSR

Allows further exploration of effects of React and OCaml

React has been influenced by OCaml and some functional programming concepts from the start. Such as immutability, purity and eventually algebraic effects.

Creates the base implementation for Server components, which are a deal breaker for server-reason-react. Allowing to only run components on the server and stream the output representation of it, without the client-side penalty of executing the JavaScript code, can change radically how we write our backends.

Recently OCaml 5.0 was released with the highly anticipated features Multicore and Effects. These new features enable the possibility of exploring some of React’s concepts to be written in OCaml.

Why you should not use it

Here are main reasons why I would not adopt server-reason-react today:

- It’s an entire new ecosystem: new language, new package manager, new trade-offs

- The learning curve might be big. The tradeoffs made by OCaml do not match with some by JavaScript (or node). Probably not as big as learning how to deal with a borrow checker 😛

- Not everyone needs this. At ahrefs it made a lot of sense, but this it may not for you.

- It is still very experimental

- Requires to lift the ecosystem to work on the server, so all client-side libraries need to be ported to OCaml when needed or stub

- Smaller community, but growing

Final thoughts

I intentionally didn’t mention how this is compiled, because I want to keep it short and explain Melange in future blog posts. For reference: ahrefs is now built with Melange

This has been very fun and I hope I can keep pushing this stack further. If you are as excited as we are, come talk to us!

Thanks for reaching the end. Let me know if you have any feedback, corrections or questions. Always happy to chat about any topic mentioned in this post, feel free to reach out.